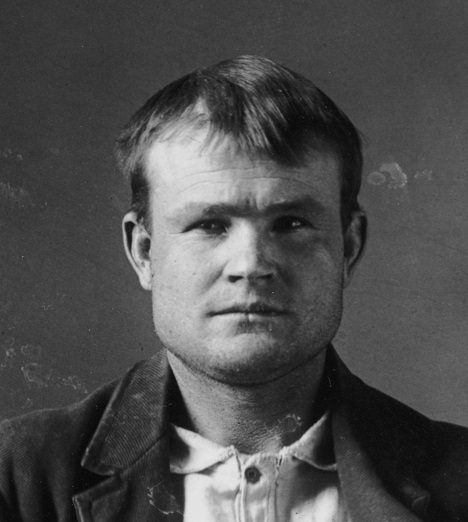

Butch Cassidy

Robert Leroy Parker, better known as Butch Cassidy, actually did walk and ride these streets. He bought cigars and groceries at Welty’s General Store, has been tagged in a photo of the original post office, and owned ranch property north of town. He dealt at (but never robbed) the old red stone bank. Some local guides identify structures in the woods as hideouts for the Hole in the Wall gang. A few old-timers have insisted that they saw and spoke with Butch here after he was reportedly killed in South America.

Robert Leroy Parker, better known as Butch Cassidy, actually did walk and ride these streets. He bought cigars and groceries at Welty’s General Store, has been tagged in a photo of the original post office, and owned ranch property north of town. He dealt at (but never robbed) the old red stone bank. Some local guides identify structures in the woods as hideouts for the Hole in the Wall gang. A few old-timers have insisted that they saw and spoke with Butch here after he was reportedly killed in South America.

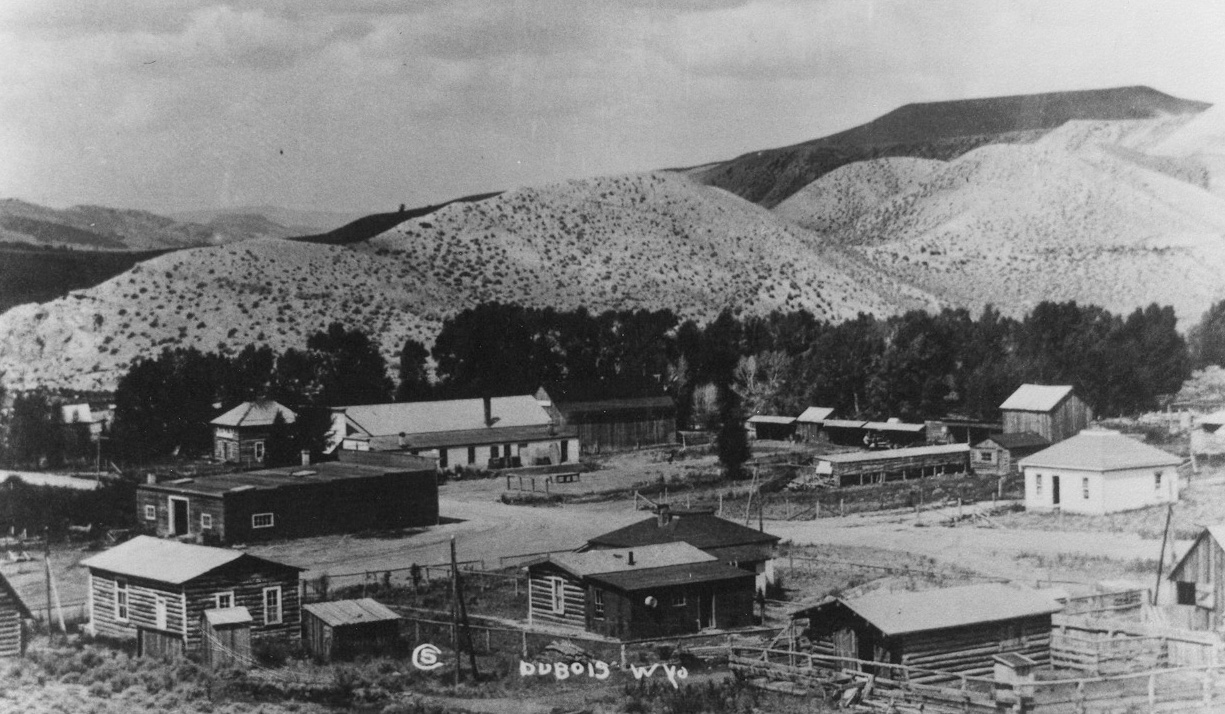

Downtown Dubois

The center of Dubois may look like it dates from the founding of town a century ago, but many of the buildings are new. However, many of them have a long history:

St. Thomas Episcopal Church, just east of the main intersection, still uses the same quaint log building constructed by tie hacks in 1910. It dates to 1901, when missionary Rev. John Roberts decided to serve the small settlement farther up the Wind River as well as Native Americans on the Reservation.

St. Thomas Episcopal Church, just east of the main intersection, still uses the same quaint log building constructed by tie hacks in 1910. It dates to 1901, when missionary Rev. John Roberts decided to serve the small settlement farther up the Wind River as well as Native Americans on the Reservation.- Also at the main intersection, the former Ramshorn Inn now houses the Nostalgia Bistro restaurant and a liquor store. Built in 1913, by a family that had homesteaded here since 1901, the Stringer Hotel (later renamed the Ramshorn Inn) ceased operations after World War II.

- The Cowboy Café began business in 1939 with the name “Hub’s Hut.” Many names later, the cafe is still a hub in the community.

- Tukadeka Traders and Horse Creek Station, a log building constructed in the 1930s, began as a café. It has been maintained close to its original design, and today features a beadwork and gift shop as well as an art gallery. Owner and sculptor Monte Baker often plays ragtime on the old piano out front.

- Both taverns, the Rustic Pine Tavern and the Outlaw Saloon, operate out of the original buildings. The Rustic, built in 1919, long hosted community meetings in its dance hall and lodgers upstairs. The building that became the Outlaw, constructed in 1934, later burned to the ground. Its dance hall survives as the existing bar.

- The old red stone Amoretti and Helmer bank, constructed in 1913 of stone quarried in the area, operated until the death of manager E. B. Helmer in 1927. It was later discovered that he had embezzled funds. This was the last privately owned bank in Wyoming.

- Welty’s General Store opened here in 1903, after operating 3 miles to the north for more than a decade. It has been remodeled often. The present structure was built by former tie hacks in 1956. The stock has changed little since the early days, although groceries are no longer for sale despite what it says on the large sign. Its most famous customer was Butch Cassidy. The store is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- What looks like a cave across the street from Welty’s was a cold-storage locker blasted out of the sandstone early in the last century. It is now unsafe to enter, because the ceiling is soft and crumbling.

Printed guides to a historic walking tour are available at the Dubois Museum and the Visitor Center. Some buildings also have signs with QR barcodes linking to historic descriptions that you can read on your cellphone.

Native Americans

The ancient Mountain Shoshone who lived here first left no written records, but many tantalizing traces remain.

- In the valley known as Whiskey Basin you can see many mysterious petroglyphs, fantastic rock art images carved with great effort and skill by unknown hands.

- In the nearby mountains, prehistoric natives left hunters’ blinds and sheep traps constructed with fallen limbs and branches, which they used to capture the bighorn sheep that were a major part of their diet.

- Up in the badlands far beyond the town dump and recycling center lies a collection of teepee rings, stone circles that once supported Native American dwellings.

All of these artifacts are precious, vulnerable, and difficult to find. Visit the Dubois Museum for information about scheduled treks or guided tours.

Tie Hacks

In a sense, the railroads start from here. Immigrants from Scandinavia worked in the area during and between the World Wars (1914-1946), hand-hewing more than 10 million railroad ties that linked the East to the West. By the 1920s, Dubois had become the largest tie-hack center in the United States.

It was hazardous work, yet most tie hacks survived. They felled the trees, removed the limbs, and cut the logs into 8-foot planks. During the spring snow-melt, the logs were spilled down to the Wind River through narrow hand-cut wooden channels called flumes. (The picture shows the remains of one flume). At the river, agile loggers would “ride” the floating logs and pole them along to prevent logjams. At Riverton, the logs were loaded onto railroad cars.

It was hazardous work, yet most tie hacks survived. They felled the trees, removed the limbs, and cut the logs into 8-foot planks. During the spring snow-melt, the logs were spilled down to the Wind River through narrow hand-cut wooden channels called flumes. (The picture shows the remains of one flume). At the river, agile loggers would “ride” the floating logs and pole them along to prevent logjams. At Riverton, the logs were loaded onto railroad cars.

The tie hacks and their families lived in mountain villages up the Dunoir Valley and later on Union Pass. Some tie hack cabins and remnants of dams and flumes can still be found along mountain trails. For more information, visit the Dubois Museum.

For a few years during World War II, German and Austrian prisoners of war volunteered to work as tie hacks in a separate camp. It is among the best-documented of many POW camps in the American West.

A memorial to the tie hacks is located about 18 miles west of Dubois, on the south side of Highway 26/287.

Union Pass

At 9,210 feet in elevation, Union Pass is a mountain hub. Three great Wyoming mountain ranges—the Wind Rivers, the Gros Ventres, and the Absarokas—ascend gradually in different directions. From the top of the Pass, you can see all three ranges at once. The Pass is also where three great river systems begin: the Colorado, the Columbia, and the Missouri. From these headwaters, they flow toward the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic via the Gulf of Mexico.

The pass was an important mountain crossing to prehistoric Native Americans, and later to early American explorers and mountain men, including the Jacob Astor party in 1811.

Easily reached by a good-quality gravel road about 15 miles west of town (look for the sign and historic markers on the south side of the highway), Union Pass is crossed by the Continental Divide trail. The Union Pass Monument, about 15 miles beyond the cattle guard and parking lot at the far edge of a small residential settlement, offers many signs with information about the ecology and geology of the area.

You can drive across the Pass in your car during the snow-free months, and the road is a snowmobile trail from December 1 until the snow melts. Look for massive carpets of wild flowers in the spring, herds of antelope and deer in the summer or fall, vast pristine fields of snow in the winter, and spectacular views everywhere up there, all the time.